From pv magazine print edition 6/24

Curtailment is becoming an increasingly important issue for the power sector, particularly as the share of solar and other intermittent-generation renewable energy sources continues to grow.

At small volumes, curtailment rarely poses a major issue for solar plant operators, or for the financial viability of projects. This is mainly because most jurisdictions continue to offer “take-or-pay” contracts that shelter PV project owners, either in part or in full, from revenue losses associated with curtailed electricity output.

In larger volumes, however, curtailment has the potential to undermine the economics of new solar projects, significantly increasing investment risk. Unlike in the past, when solar projects were financed via long-term contracts in the context of auctions or feed-in tariffs, many sites are now being financed either via bilateral power purchase agreements (PPAs) or on a merchant basis, which involves selling energy on the open market. Uncertainty about the volume of electricity that could be curtailed directly increases the cost of capital for PV projects and, in turn, puts upward pressure on the cost of solar. Furthermore, a perception that solar output is being “wasted” could gradually erode public support for further PV deployment, particularly if the curtailed volumes grow substantially.

Deep cuts

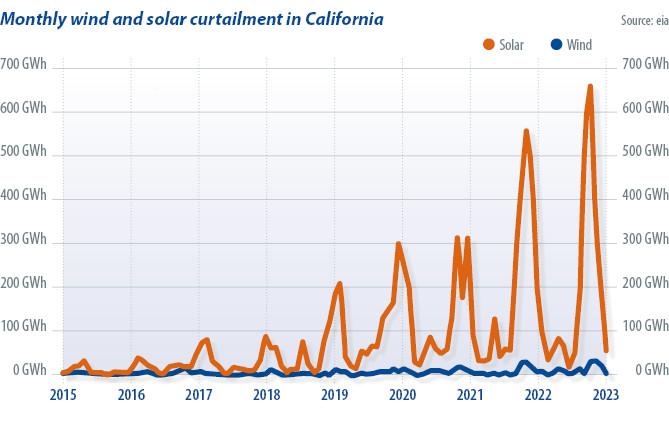

Data from a selection of markets show that curtailment is on the rise. In Chile, the curtailment of solar has increased significantly in recent years, affecting 1.4 TWh of output in 2022 – roughly 1.8% of annual electricity demand – and nearly 800 GWh in the first five months of 2023. In parts of Australia, curtailment has grown from roughly 4%, in the first quarter of 2022, to more than 7% in the opening three months of 2023, with certain days posting curtailment levels nearing 20% of total available PV output. In Cyprus, PV curtailment has grown from just over 3% of generation in 2022 to more than 13% in 2023. In parts of the United States, curtailment is also on the rise: in Texas, 9% of the output from utility scale solar was curtailed in 2022. In California, more than 3% was curtailed in the same year. In Germany, the curtailment of solar amounted to almost 2% of total PV output in 2022.

At its core, curtailment is a symptom of an insufficiently flexible power system. Fortunately, experience shows that curtailment can be avoided or significantly reduced through policy. Particularly during the early phases of PV penetration – when up to 10% of power generation comes from solar – there are often other, lower-cost flexibility options available.

At this early stage, the toolkit includes measures such as reducing the must-run hours of fossil-fuel-based power plants; increasing the flexibility of other power generation sources, such as hydropower or biomass; moving toward economic dispatch; introducing intra-day electricity markets; and improving both demand and solar output forecasting.

Broader toolkit

At higher shares of solar generation, a broader toolkit is starting to emerge. Measures include increasing the flexibility and responsiveness of power demand, introducing combined procurement of solar-plus-storage systems, encouraging new business models such as virtual power plants and aggregators, introducing more dynamic electricity pricing, including locational pricing, and making greater use of surplus electricity in the transport and heating and cooling sectors.

Basic economics are also helping as periods of electricity oversupply lead to lower prices, which in turn makes it more attractive to consume electricity. In South Australia, the power system experiences sub-zero electricity prices almost 60% of the time between roughly 11:30 am. and 2 pm. With the continued growth of solar, and without a significant scale-up of demand-side flexibility, markets such as South Australia will start facing repeated periods where daytime electricity prices are permanently negative between 10 a.m. and 4 pm.

In response, the government and power utilities have started implementing measures to encourage greater flexibility, including through demand-response-enabled pool heaters and air conditioning units, variable electricity pricing, and flexible electric vehicle charging.

Not all negative

From a power system standpoint, curtailment should not be thought of purely in negative terms. It can also contribute to power system flexibility in a manner that can be activated relatively easily to maintain system stability.

In fact, it may be less expensive for solar project operators – as well as for the system as a whole – to curtail PV output occasionally than it would be to build out large-scale energy storage or power grids to ensure that solar output is never curtailed.

With the share of solar rising in virtually every country around the world, it is time for a wider debate about curtailment, how to bind it contractually, and how curtailment itself stacks up both in technical and economic terms against other ways of balancing energy systems. As the world progresses toward its second terawatt of installed solar generation capacity, and beyond, this debate is only going to grow in urgency and importance.

About the authors: Toby Couture is the founder and director of E3 Analytics, an independent renewable energy consultancy in Berlin, Germany. He has 15 years’ experience in the sector and has advised dozens of national and state governments throughout the world on renewable energy policy, strategy, and finance.

About the authors: Toby Couture is the founder and director of E3 Analytics, an independent renewable energy consultancy in Berlin, Germany. He has 15 years’ experience in the sector and has advised dozens of national and state governments throughout the world on renewable energy policy, strategy, and finance.

David Jacobs is the managing director and founder of International Energy Transition GmbH (IET). He has 20 years’ experience in energy policy design, authoring more than 100 publications. He has advised policymakers in more than 40 countries.

David Jacobs is the managing director and founder of International Energy Transition GmbH (IET). He has 20 years’ experience in energy policy design, authoring more than 100 publications. He has advised policymakers in more than 40 countries.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Adequate S2S (Sunrise-To-Sunset) Energy is needed to avoid / minimize curtailment and ensure 24hr/DAY Pollution Free Solar Electricity.. This S2S Energy Storage comes to about 25-30% of the Installed Solar / RE Capacity..

Which NATION can claim to have this today… and are always catching up to the demand… in this case by curtailment…